It's a bird! It's a plane! No, it's a drone hovering above Guy Wicks Field at the University of Idaho in Moscow.

Just minutes earlier, a group of about 20 students stepped out of the Agricultural Engineering Building into the bitter cold wind of an early April afternoon and headed to the field to set up for today's lesson. With checklists in hand, they're ready to practice piloting three drones, from small entry-level models to the $40,000 Astro model drone produced by Firefly, a company based in Woodinville, Washington.

The students take turns practicing a list of maneuvers and training protocols. They're learning to use drones for hobby or in career paths, like photography or agriculture.

Drones, also known as unmanned aerial vehicles or unmanned aircraft systems, have drawn international attention for their transformation of warfare — the New York Times reports that 70% of injuries and deaths in the Ukraine-Russia war are now caused by drone attacks.

In the United States, you may have heard of the UFO sightings that caused public concern in New Jersey in 2024. White House officials later confirmed that the unidentified flying objects were part of a Federal Aviation Administration research project using drones.

While drones first appeared in the 1930s — the British Royal Navy coined the term "drone" with bees in mind when they named the unmanned aircraft they used for target practice — the technology has improved dramatically over time, both for military and personal use.

Since 2013, everyday people have been able to buy hobby drones to take photos and videos, and developments in recent years have allowed for improved GPS, HD video, longer battery life, and anti-shake technology to permit crisper images.

Now, even greater advancements in drone technology allow for a wide variety of applications, from law enforcement to scientific research.

The Spokane Police Department uses drones to mitigate risks to officers looking for potentially dangerous suspects, and to help with search and rescue operations.

Content creators and photographers in the region have added drones to their photography arsenal for real estate shoots and filmmaking, catapulting what was once a hobby into a robust industry.

Washington's Department of Fish and Wildlife uses drones to track fish and rabbit nesting grounds and to identify habitat for restoration. The Washington Department of Ecology has also used drones to help prevent exposure to harmful chemicals while tracking environmental hazards.

Agricultural scientists at Washington State University are developing drone systems to protect crops from animals.

And, at the University of Idaho, professors have developed a drone curriculum to prepare students for roles as certified drone pilots in various applications.

DRONE LAB

The University of Idaho developed its drone lab, which is run by Jason Karl, a professor of rangeland ecology, in late 2017. Through the lab, Karl teaches students about the various tools they'll need for aerial-based research, from using software systems to operating unmanned aircraft systems.

The lab offers courses on safe piloting, FAA regulatory compliance, and data collection and analysis. It also supports other university research in areas such as crop health mapping, post-fire recovery, and herbicide application.

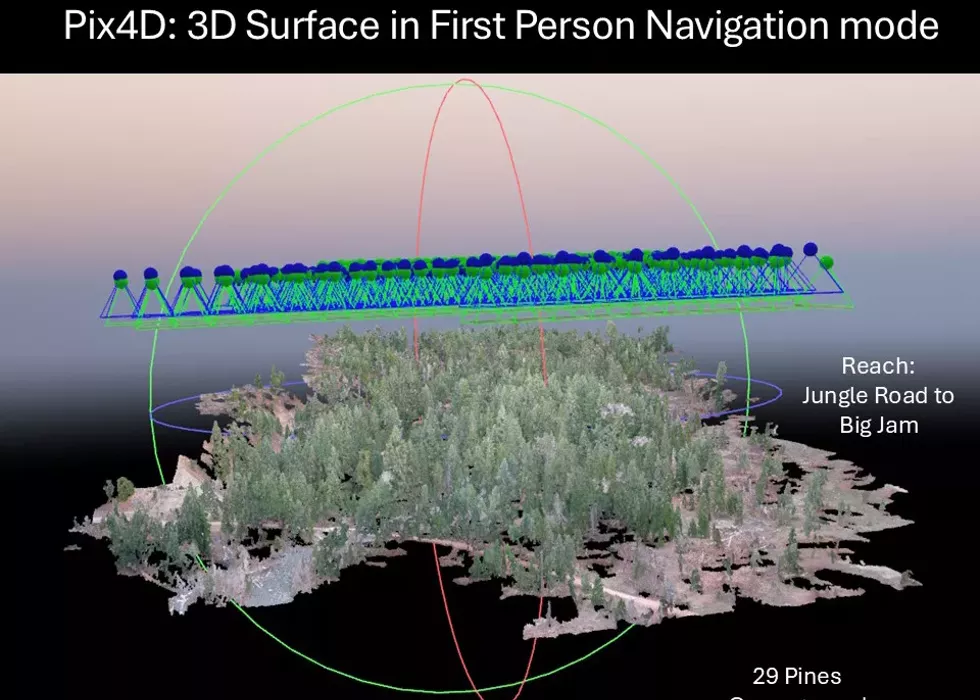

With a $110,000 grant, the lab purchased a drone-carried light detection and ranging system, commonly known as LIDAR, putting it on the cutting edge of research sciences. LIDAR uses an advanced sensor that emits laser pulses and measures the time it takes for the reflected light to return, enabling precise mapping of hard-to-access terrain.

Karl has mapped geographic information systems for 30 years. Previously, it was expensive to find an airplane to produce aerial imagery for analysis. He says drones have democratized the field and made aerial mapping available on demand.

"You can do some great, high-quality mapping with a fairly reasonably affordable drone — like $1,000 — and you can go out and get that imagery whenever you need it," Karl says. "It's really opened up that flexibility of getting the imagery you want, at the place you want, when you want it, in a way that was never really affordable or possible before."

Karl says University of Idaho's drone lab is working to become the Inland Northwest's hub for drone use. Before its founding, there was a hodgepodge of research drone users with different equipment and skill levels. As software and sensors become more complex, centralized drone facilities become essential to understanding how to use the technology for advanced research.

The goal is to go beyond flight training to also teach researchers and students to use software, collect data and interpret that data, he says.

"The easiest part of the whole process is to go fly a drone and collect a bunch of data," Karl says. "The hardest part of the process is actually analyzing that data and interpreting it."

University of Idaho's drone lab classes include students from different degree programs, including many studying precision agriculture, which focuses on crop systems, nutrient management and irrigation. Karl says students from geography and engineering also participate in the courses.

Beyond students in STEM programs, the lab's courses have attracted journalism and mass media students interested in using drones for cinematography.

Back on Guy Wicks Field, students are setting up a drone course and running through their checklists for aerial maneuvers. They're reviewing how to angle their drone, and checking the rotate and dial down button sensitivity settings to make sure their image capturing will be smoother.

One student eager to test the pricey Astro drone is Katherine Mo, a fine arts graduate student who's been interested in flying quadcopter drones from a young age. Mo says they're taking the course to prepare for FAA certification and to ultimately fly commercially for photography services.

The Remote Pilot Certificate, known as Part 107, is the certification you receive after passing the FAA certification test. Karl says the lab prepares students for that test and also teaches them how to pilot.

The best way to think of the certification test is the equivalent of a written test for a driver's license.

"You can get your FAA remote pilot certification without ever having flown a drone at all, it's just a knowledge test — it's not a skills test," Karl says. "We try to provide as much experience as possible flying all sorts of drones, from little Tiny Whoop [drones] that you fly indoors, all the way up to big agricultural spray drones that weigh 100 pounds."

Even with all the advancements in technology and training, Karl says improvements to payload or battery life are still a concern for scientific drones, but the future looks promising. He predicts, for example, that we will eventually see significant agricultural businesses like John Deere developing systems to automate drones for spraying crops.

"I think that once we start to get more integrated systems, where the software and hardware are a little bit better developed and integrated, you'll start to see these companies getting into that as well," Karl says.

FROM REAL ESTATE TO FILM

The Inland Northwest is a beautiful place to live and work, and many hobbyists and professional photographers capture its beauty every day. The affordability of drones as tools for cinematography and panoramic photos has allowed local photographers like Teuvo Orjala, owner of Fixed Focus Media, to capture visually stunning images of Spokane and Coeur d'Alene.

Orjala's background is in design and multimedia arts. When he first learned about popular Chinese drone manufacturer DJI's latest Phantom 4 drone, he knew it was the next frontier for photography. He sold one of his electric guitars for $1,800 to buy his own Phantom 4.

Orjala quickly looked into the FAA regulations and pursued certifications to be able to use the drone for business. He learned the information required for testing, which he passed, and tracks state, county and city regulations that he may need to know for his drone photography.

He's used his drone to cover protests in Spokane and has spoken to FAA officials about the rules for drone use during thunder and lightning storms. For instance, he says you're not allowed to fly a drone at night, when your line of sight is obstructed.

"I feel like the FAA has been really great about working with drone pilots and our [photography] industry," Orjala says.

Orjala has been able to use images he's captured via drone for art shows, as well as commercial and real estate work.

"I'm a professional high-end real estate photographer," Orjala says. "Whenever I go out to shoots like that, I photograph the property, [and] I'll also photograph big lots of land for some businesses. But I've also been hired to shoot for movies."

Orjala's drone pilot license has allowed him to accept gigs from production and documentary companies because he has the knowledge and ability to safely and legally shoot these videos with drones.

He says the widespread acceptance of affordable DJI drones, however, has also created new concerns. Less experienced hobbyists may violate privacy rules while using the consumer-grade drones. Orjala says he tries to educate those he sees violating privacy rules about local laws and FAA regulations.

Overall, Orjala says the possibilities for creativity with drones will continue to grow in film, real estate, and business photography, and he sees continued growth in those areas.

"I feel like there's infinite room to grow for people in this space," Orjala says. "Every movie you watch, every documentary, drones are flying all over the place."

LAW ENFORCEMENT

The Spokane Police Department began using drones in early 2019, and now has a small fleet that includes seven drone pilots with their own assigned drones. Spokane police Lt. Jay Kernkamp says the team can also use interior drones, which are optimized for enclosed spaces inside buildings.

The police department has also acquired a $164,000 Dragonfish drone from Autel, a Chinese competitor to DJI. Kernkamp says the department bought the drone in 2024 with federal grant funds.

The police department primarily uses drones to enhance officer safety and provide de-escalation. Drones provide aerial views to help officers formulate safe response plans.

The second purpose is for search and rescue missions to help gain a wider visual when looking for missing persons, vulnerable adults, or runaway children, Kernkamp says.

"Anything that may be high risk that we could enhance our response to and make the community safer, we'll try to utilize a drone," Kernkamp says. "It's a lifesaving measure, because we can locate somebody so much quicker."

Kernkamp says the department's drone pilots who go out with SWAT teams are all FAA Part 107 certified and can be deployed as a more effective means of operating. After a search warrant is obtained for a situation where someone's barricaded themself inside, he says drones can be used to enter the building and make sure it's safe before an officer enters.

Groups like the ACLU are concerned that law enforcement could use drones to surveil or track individuals, but Kernkamp says the department's rules prevent that. However, officers will use drones in cases when counterprotesters are potentially engaging in violence with protesters. Drones can help officers identify problematic groups that might target protesters within a sea of people, he says.

"We're not going to use drones as a surveillance tool on individuals expressing their freedom and their [First] Amendment rights," Kernkamp says.

He notes that newer drones specialized for law enforcement are equipped with police markings and a public address system and can provide more direct communication with people on the ground. He says it won't replace face-to-face contact when it's needed, but in certain lower-risk situations, it makes communities safer.

Kernkamp wants the public to know that police realize that trust is paramount regarding drone usage and that the department follows all regulations.

"I think we try to abide by best practices and FAA regulations, and are very critical of ourselves and making sure that we don't lose the public's trust," Kernkamp says. "[We're] trying to keep the community as safe as possible by utilizing new technology."

AN EYE ON CROPS

Head west from the University of Idaho, not to Washington State University's main Pullman campus but to its extension site in Prosser, near the Tri-Cities, and you'll find researchers there using drones to monitor and manage crops.

Lav Khot is an assistant research professor in biological systems engineering at WSU Prosser, which is also called the Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center. His research focuses on analyzing biotic and abiotic stressors on crops grown in Washington.

Living organisms like fungi, bacteria and insects are forms of biotic stressors. Abiotic stressors include extreme temperature, drought, salinity and nutrient deficiencies.

New drone imagery has allowed for "prescription mapping" of sorts for these crop stressors, allowing Khot to identify areas that need to be treated for water stress, irrigation leaks, canopy issues, or soil temperature differences.

"We can collect a lot more meaningful data now with multispectral and hyperspectral thermal imaging sensors that we can put on the platform," he says. "Thermal imagery is good for looking at the irrigation leaks and things of that nature."

Drone technology has also advanced to include spray drones for field crops. When testing drones to spray chemicals on orchards and vineyards, tree canopy coverage made it difficult to achieve effective application. So researchers developed spray booms for pesticide and weed control applicators, and figured out how to get drones to haul larger chemical loads, allowing for a more precise and even spray application.

Even so, using drones for large-scale crop management isn't feasible yet due to payload limits and battery size.

"I think the bottleneck is the payload, which is how much chemical we can carry in the air, because the downtime to load and unload the tank is killer," Khot says. "If we have midsized drones with a bigger spray-carrying chemical capacity, then we would see more traction for this technology."

Khot hopes that more agricultural businesses help develop research in precision agriculture and work with growers to navigate these new drone technologies.

SCARECROWS IN THE SKY

Khot's WSU colleague, Manoj Karkee, is an associate professor of biological systems engineering who focuses on using drones as deterrents. His research, which began in 2019, has developed autonomous drones equipped with cameras to detect, scare and deter pest birds, like European starlings or crows, from destroying vineyard crops.

Think of it as a flying scarecrow.

Karkee says these drones could help Washington farmers save $80 million in crop damage caused by birds each year. He says crops with birds nesting near them or located in bird flight paths can lose 50% of their harvest some years.

Current deterrents include expensive and labor-intensive netting for vineyards and nonlethal lasers that rotate around the field. Netting can cost up to $800 for 1,000 feet, which doesn't include the labor-intensive work to install it. Affordable automated laser systems can cost from $2,000 to $10,000. Karkee says birds can also quickly adapt to predictable lasers.

We're actually putting a drone together ourselves, buying components from the market, and these components are mostly sourced from U.S. companies.

"Birds are pretty intelligent, and they find ways to get around it, go under it, and get into the field pretty quickly," Karkee says. "Some of the affordable technologies are not very effective, while the netting, being the most effective, is pretty cost-prohibitive."

After using manual drones to deter birds on mornings when the animals were most active, Karkee studied the damage to fruit crops. He says the research demonstrated the drones reduced grape loss sevenfold.

The research then presented a new question. What if we could program software to fly the deterrence drones autonomously?

"We looked into the possibility of doing it autonomously, using cameras to find out where birds are flying into and then having automated drones that would fly into the fields and make specific patterns of flights to scare birds away," Karkee says.

The initial research into autonomous systems shows promising results. Karkee says the next step is to scale up that research to work with more drones and growers, testing across multiple fields to show the long-term resilience of bird deterrence. He also wants to test other methods, such as emitting predatory sounds and changing flight patterns, to prevent birds from learning the systems.

However, with progress comes new obstacles. Karkee is concerned about multiple efforts in Congress to ban the use of federal funding to purchase Chinese-made drones. The Countering CCP Drones Act, which passed the House but not the Senate in 2024, would have specifically added DJI drones to the FCC covered list, denying DJI devices from accessing U.S. communications infrastructure.

Congressional supporters of the bill expressed concerns that DJI equipment may be sharing sensitive data with the Chinese Communist Party.

The law would target the popular line of drones produced by Chinese technology firm DJI, which helped catapult the use of hobby drones with release of its Phantom 1 in 2013. Karkee said the law would've impacted his earlier research, which used DJI drones, but now his team plans to build their own drones to comply with the regulation.

"We're actually putting a drone together ourselves, buying components from the market, and these components are mostly sourced from U.S. companies," Karkee says.

HELPING FIGHT FIRES

Washington's Department of Ecology uses drones across the state to monitor and analyze a variety of environmental concerns, including methane emissions, mining site hazards, subsurface landfill fires, coastal erosion and brownfield site cleanups.

Brad McMillan is the unmanned aircraft system program coordinator at Ecology and oversees a centralized drone program based in the IT and GIS departments. He oversees a team of 15 drone pilots that could grow as more pilots become certified.

McMillan says the department adheres to FAA regulations and internal policies, ensuring safe and transparent operations. Like many agencies, they primarily use DJI drones but are exploring alternatives due to potential bans on the Chinese-made products.

"I think it's something like over 75% or even higher than that of DJI drones that are being used by state agencies, public entities and first responders," McMillan says. "They're all DJI because it's hard to find anything that's comparable."

One of McMillan's newest acquisitions is a Skydio X10 drone. The drone company, the largest in the U.S., proudly claims to be designed, assembled and supported in the USA. However, Skydio relies on Chinese manufacturers for its lithium-ion batteries and other components used in drone building, according to industry leaders.

This specific model utilizes a myriad of components that provide thermal and photogrammetry imaging. Photogrammetry is a technique that uses aerial photos to create detailed 3D models of a site with geographic details like hills, rivers and plateaus.

Instead of taking eight hours and three people to [cover] 25 to 30 acres, we can do a 20 to 30-minute [drone] flight and see the imaging...

Ecology uses drones with thermal imaging for projects like monitoring the Eastern State Hospital landfill in Medical Lake. In August 2023, the Gray Road wildfire ignited an area of old construction and demolition debris above the landfill and ultimately underground.

The fire district was unable to extinguish the underground fire using water, so it needed to be extinguished by digging up the debris. Understanding the full extent of the smoldering material was important to keep workers safe and ensure all hot spots were finally fully extinguished in September 2024.

"Landfills that have a subsurface fire underneath, we can't send our staff out there to go and walk across these landfills, because it's too dangerous," McMillan says. "So we send our thermal drone out there to go and detect hot spots on the ground to detect if this fire is actually burning."

While Ecology mostly uses drones for photogrammetry, GIS mapping, and analyzing work sites, the department also uses them for LIDAR technology, which McMillan says helps with looking at coastal erosion along the Pacific and parts of Puget Sound.

The drones' advanced cameras also provide a bird's-eye view of oil or hazardous substance spills, which helps ground crews effectively coordinate spill responses across the state. He says the thermal signature of oil slicks is different from surface water, and drone imagery helps identify features that the naked eye may miss.

Another application for drones could be for air quality monitoring, using multiple air sensors directly connected to a drone to provide data. McMillan says Ecology is still in the early stages of utilizing air quality drones, but he expects to see them used over landfills and methane release sites, and to detect other toxic substances being released into the air.

SAVING WILDLIFE

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife also uses drones for research and habitat monitoring, including work by one of the department's biologists, William Meyer, in the Yakima Basin.

Meyer's research centers on monitoring 15 bull trout populations in the basin, five of which are critically low. He uses drones to survey and track species' habitats, documenting changes in river systems and identifying areas where the fish are struggling.

During droughts, Meyer and his team conduct rescue operations, moving fish from dry stream sections to safer water environments and collaborating with the Yakama Nation to rear and release fish back into their native streams.

"For some of those populations I study, we have upwards of a mile of the stream that will dry every year during droughts," Meyer says. "Fish that get stuck in those dry areas, we go out with rescue crews and try to get them out at night, because they're more peaceful."

Joshua Rogala is also a biologist with Fish and Wildlife who complements Meyer's work by using drone technology to map and analyze river systems. He captures detailed aerial imagery that helps track habitat changes, measure stream volumes and identify potential restoration sites.

Rogala's drone use allows him to efficiently cover large, remote areas that would be challenging and time-consuming to survey on foot, providing research that's crucial for understanding and mitigating the environmental challenges facing bull trout.

"An aerial picture can tell you a lot more of what's going on," Rogala says. "The measurement tools that come along with the drone image processing are able to take volumetric measurements, linear distance measurements... instead of me having to run a field tape for a couple thousand meters."

Meanwhile, Fish and Wildlife's Miranda Crowell and Carissa Turner research the Columbia Basin pygmy rabbits. Their primary work involves using drones to monitor and conserve the critically endangered rabbits, which live in sagebrush in Washington.

Pygmy rabbit populations are severely impacted by habitat loss due to agricultural expansion and invasive grasses. During the winter, Crowell and Turner use drones to track rabbit populations and identify tracks, dramatically reducing the time they spend walking to survey the land.

"Instead of taking eight hours and three people to do 25 to 30 acres, we can do a 20- to 30-minute [drone] flight and see the imaging and the tracks in the snow," Crowell says.

The pygmy rabbit population is fluctuating, with numbers as low as nine in winter 2018-2019. Drones also allow research teams to keep a safe distance to avoid disturbing the animals and can help with reintroduction plans that allow rabbit kits to be placed in areas where they can thrive.

The pygmy rabbit team looks forward to finding more applications for drones in their restoration work.

"We are trying our best to use all the tools we can and do it in a safe way," Crowell says. "We're always trying new things to enhance our research, our studies and enhance our monitoring the best we can." ♦